Adam I, Adam II: On Building, Being, and Living Life Well

Several years ago, I came across a framework for thinking about life that’s stuck with me.

The framework came from Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik’s 1965 essay “The Lonely Man of Faith.” I learned about it from David Brooks in his book The Road to Character. (Check out my AoM podcast interview with David, where we discuss this book. It’s one of my favorites.)

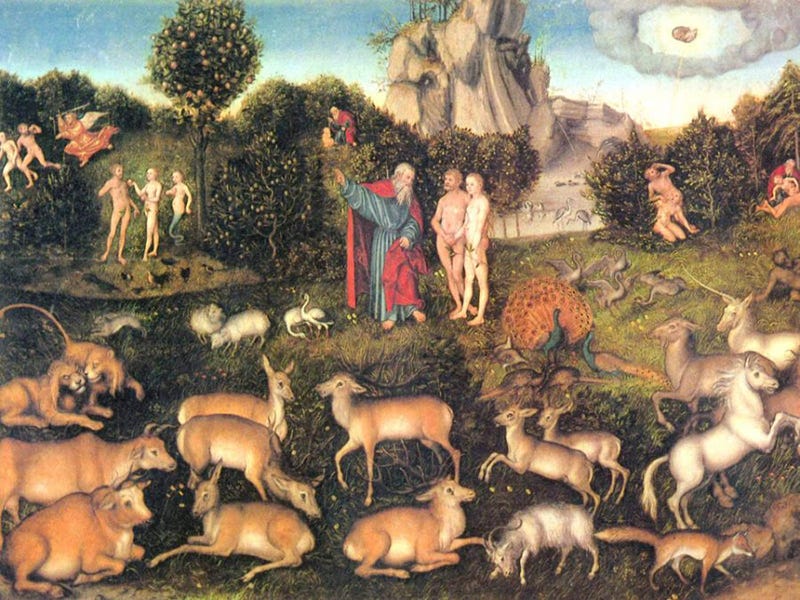

In “The Lonely Man of Faith,” Soloveitchik describes two archetypes that live inside every human being. Both are drawn from the first two chapters of Genesis.

People often overlook this, but Genesis contains two versions of the creation story.

In the first creation story found in Genesis 1, God makes man in His image. He tells Adam to “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.” Adam is given dominion over the rest of creation and tasked with shaping the material world, bending it toward order and usefulness. Soloveitchik calls the Adam in the first creation story Adam I. He’s Adam the maker, the builder, the achiever.

Also, in this first version of the creation story, Adam isn’t alone. He was created alongside Eve at the same time. Male and female created He them. He and Eve are co-laborers, charged together with ordering and subduing the earth. Adam I’s social world is one of coordination, enterprise, and shared achievement.

Adam I reflects what Soloveitchik calls the “majestic man.” It’s the part of us that invents, organizes, and masters. He mirrors God as Creator, shaping chaos into order.

The second creation story gives us a different kind of Adam. In Genesis 2, God forms man from the dust of the ground, breathes life into his nostrils, and places him in the Garden “to till it and keep it.” He doesn’t tell this Adam to subdue the earth — just tend to this small corner of it.

Unlike Adam I, this Adam, Adam II, begins life in solitude. God creates him alone, and only later, seeing that “it is not good for man to be alone,” brings another person into the picture. For Adam II, relationships weren’t about doing things; they were about being known. The Adam and Eve in this version of the creation story have a relationship that’s not so much instrumental as existential. They’re soul mates. Flesh of each other’s flesh. They keep each other company in a world that can feel awfully lonely.

Soloveitchik calls this figure Adam II. Adam II’s life isn’t about acting on the world; it’s about responding to it. Formed from dust, Adam II knows he’s not self-sufficient. He’s a creature who receives rather than creates. He’s charged with care, not conquest. His meaning doesn’t come from what he builds, but from the relationships he tends to, specifically those with God and Eve.

Taken together, these two Adams represent two sides of our nature.

Adam I is the part of us that wants to build — to leave a mark, to turn potential into reality, to make the world a little more orderly than we found it.

Adam II is the part of us that wants meaning — to be overcome with awe, to surrender ourselves to something bigger.

In The Road to Character, Brooks calls the virtues of Adam I resume virtues; the virtues of Adam II, eulogy virtues. Resume virtues are the things we put on our application to get a job. They’re our outward achievements. Eulogy virtues are the things we want people to say about us at our funeral: he was kind, he was a good husband and loving father, he lived by his principles.

One of Soloveitchik’s points in “The Lonely Man of Faith” is that a flourishing life requires cultivating both Adam I and Adam II. The trick is figuring out when to focus on one Adam over the other. Learning to balance the two Adams inside of us is an essential part of the art of living well.