Nietzsche's Last Man Wears a WHOOP Band

How the mustachioed thinker and other philosophers predicted our sickly obsession with health

A few years ago, I was on my usual morning walk around the neighborhood at 6 AM. The street was quiet except for an Amazon delivery van making early morning Prime drop-offs.

I stopped in the middle of the street and looked up at the dawn sky.

I wasn’t praying or meditating on nature’s beauty.

No, I was trying to get “low solar angle photons” to hit my retinas to entrain my suprachiasmatic nucleus to release a timed pulse of cortisol and sync up my circadian rhythm so I could sleep better at night.

At least that’s what modernity’s oracle of health, neuroscientist Andrew Huberman, said would happen if I stared at the morning sky like a 19th-century Millerite awaiting the Second Coming.

You see, I had been having some trouble sleeping. I used to sleep like a baby, going to bed at 10:30 PM and waking up at 7 AM without a single interruption to my rounds of blissful nightly unconsciousness. But when I turned 40, I started waking up at 4 AM and had trouble going back to sleep. I was willing to do anything to get a full night of sleep. Even staring at the rising sun.

Sadly, the photons didn’t help my sleep (though listening to fake radio baseball games did).

Looking at the morning sky to improve my sleep wasn’t my first foray into “biohacking.” Over the years, I’ve experimented with a bunch of tactics and gizmos to improve my “wellness.”

Nootropics? I’ve tried a few.

Cold showers? I wrote an article about them way back in 2009, a decade before cold exposure hit mainstream popularity.

“Greens” supplements? I’ve swigged them. They taste like how my grandpa’s barn in New Mexico smelled. That is, like hay.

Tracking devices like WHOOP bands and Oura rings? I own them. They largely sit in my desk drawer unused.

I’ve tried all this biohacking stuff in the hopes that it would improve my health and vitality, but I’ve been an ambivalent practitioner. In fact, I’m embarrassed about it. When I take a step back and look at my biohacking efforts through the lens of Adam Smith’s “Impartial Spectator,” I think, “This is kind of weird.”

The weirdness extends to the culture at large. I’m hardly alone in my health experiments. There’s been a lot of popular interest in the last decade in how to optimize one’s workouts, diet, and sleep, and extend the lifespan. People are not only increasingly focused on how to improve their health, but they’re paying more attention to what may be going wrong with it. Feeling unaccountably unwell, they wonder if toxic mold or Lyme disease is to blame, and chase cures that promise to restore their vitality.

This all-consuming focus on health hasn’t arisen randomly, but because of a particular set of cultural circumstances.

And it’s a phenomenon that philosophers predicted — and warned against — for centuries.

The Prophet of the Weirdness of Health Protocols

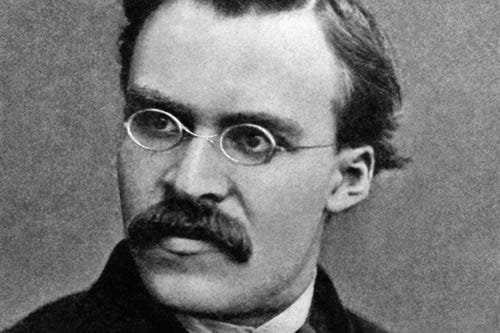

In 1883, Friedrich Nietzsche published Thus Spoke Zarathustra. It’s a fun book. It reads like an overly bombastic version of the Old Testament. It’s full of bangers like “you must have chaos within you to give birth to a dancing star.”

In it, Nietzsche explores man’s options for ordering his life after the death of God — an event he described in The Gay Science. Many people mistakenly interpret Nietzsche’s idea of God’s death as celebrating deity’s demise. But a closer reading reveals a different story. Nietzsche was simply making explicit what had silently happened in the West since the rise of modern civilization. He was describing, not exulting.

Belief in God gave people a telos — an ultimate aim — around which to order their lives. Nietzsche predicted that the death of God would bring with it the rejection of the belief in a universal moral law, causing existential nihilism — a philosophy he detested.

So how do you overcome the nihilism that fills the vacuum left by God?

Well, that’s what Thus Spoke Zarathustra is about.

Zarathustra, a wise prophet, comes down from the mountain to speak to the people. He tries to tell them about the Übermensch — the Overman or Superman — a type of person who creates, who overcomes, who embraces the tragedy and danger of life. According to Nietzsche, if you don’t want to sink into depressive nihilism, you have to become the Overman. You’ve got to create your own values and strenuously live up to them. And it’s hard.

The people that Zarathustra preaches to don’t like all this talk about tragedy and danger and having to create things. They just want comfort and happiness.

So Zarathustra warns them that the alternative to the Übermensch is a disconcertingly mediocre species of human — the Last Man:

Lo! I show you THE LAST MAN.

‘What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?’—so asketh the last man and blinketh.

The earth hath then become small, and on it there hoppeth the last man who maketh everything small. His species is ineradicable like that of the ground-flea; the last man liveth longest.

‘We have discovered happiness’—say the last men, and blink thereby.

…

Turning ill and being distrustful, they consider sinful: they walk warily. He is a fool who still stumbleth over stones or men!

…

One still worketh, for work is a pastime. But one is careful lest the pastime should hurt one.

One no longer becometh poor or rich; both are too burdensome. Who still wanteth to rule? Who still wanteth to obey? Both are too burdensome.

…

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health.

The Last Man doesn’t really care about ultimate ends. He’s indifferent to the death of God, and he definitely has no interest in creating and fulfilling his own telos to replace the divine order. He has no great passion, no great cause, no desire to rule or to obey. Too much work!

The Last Man is, in the words of philosopher Robert Solomon, “a spiritual couch potato.”

While the Last Man doesn’t have a transcendent telos, he does have a telos. It’s just really small. He wants to be comfortable, safe, and live a long time. He wants to feel good.

And what does he do to achieve that?

That last line in the quote above tells us. The Last Man has “a regard for health.”

According to Nietzsche, the Last Man fills the vacuum created by not having a transcendent telos by making health and wellness his ultimate aim.

I reckon if we transported Nietzsche to the United States in 2026, he’d see a world overrun with Last Men who see “illness as a sin.” Non-diabetics monitor their blood glucose to ensure there aren’t any glucose spikes (I’ve done this). People tape their mouths shut while they slumber to encourage nose breathing, which is supposed to improve their sleep (I’ve also done this). Rich weirdos like Bryan Johnson measure their nocturnal boners and receive blood transfusions of their young son’s blood (I have not done this).

I don’t think Nietzsche would have been especially interested in the particulars of our modern health and wellness obsession, like dudes exposing their balls to red light or people injecting themselves with peptides. But he would have recognized the Last Man behavior right away.

According to Nietzsche, we humans are creatures that will. We can’t help but will. When we don’t have big things to will towards, we will towards smaller things. “Man would rather will nothingness than not will,” said Nietzsche. Lacking higher ends, the Last Man directs his will into comfort, safety, and longevity. The only suffering people are willing to endure is that which makes their own body better.

But when your willing shrinks to just your bodily functions, life loses its vitality and tang. People busy themselves monitoring their readiness score, checking for cancer markers in their blood, and avoiding EMF radiation rather than putting their energy, bandwidth, and time into doing great deeds, making great art, and building great and lasting institutions. That’s the danger Nietzsche thought came with the Last Man’s obsession with health and wellness.

Plato and the Valetudinarians

Nietzsche wasn’t the first to notice that when health becomes the organizing principle of a life, something starts to go wrong at the personal level and then metastasizes at the social one. Plato saw this centuries earlier.

In the Republic, Plato (through the character of Socrates) tells a story of a man named Herodicus, a physical trainer who fell into poor health and responded by creating a personal regimen that blended gymnastics with medicine. Instead of either getting better or getting on with his life despite his infirmities, Herodicus made his own health his vocation. He could do this because he was rich and had no civic responsibilities. Socrates calls him a “valetudinarian” — a man obsessed with his health.

Herodicus monitored everything. His digestion. His movements. His habits. He developed elaborate routines for himself and, Socrates notes, lived in “constant torment whenever he departed in anything from them.” Reading this, it’s hard not to think of modern people who get in a funk if they fail to hit their macro targets or wake up with a poor readiness score on their fitness trackers.

So what did all that handwringing about his health get Herodicus? Socrates says Herodicus didn’t cure himself so much as he “lengthened out his death.” He lived a lingering life. He didn’t do much because all his attention was directed inward. And that inward turn had consequences. Socrates argues that overweening concern for the body actively interferes with the development of virtue. “Excessive attention to the body,” he writes, “is almost the greatest impediment of them all; it is troublesome in running a household, in military campaigns, and in positions of authority in the city.”

In other words, a man overly preoccupied with his health is a man whose soul shrivels. He becomes someone who doesn’t have the character to be a good husband or father, command an army, or take on responsibility in his community.

Socrates contrasted the rich and idle valetudinarian’s approach to health with that of the blue-collar carpenter. When a carpenter gets hurt or sick, he goes to a doctor so he can get better so he can get back to work. Health is a means to an end for the carpenter. And that end was a productive vocation. According to Socrates, if a doctor prescribes some lengthy regimen for the carpenter, like “placing felt hats on his head” (this line made me chuckle and reminded me of the felt hats 21st-century bros wear in saunas), he tells the doc to pound sand. He doesn’t have time for that. He’ll just get on with living.

Plato wasn’t against exercise and eating right. For him, the health of the body reflected the health of the soul and vice versa. Mens sana in corpore sano and all that. But for Plato, the virtue of health could become a vice when it became a person’s end all be all. Attention to health was meant to support living, not replace it.

There Is Nothing New Under the Sun

Plato recognized the dangers of the ur-biohacker, and Nietzsche hinted that modernity only exacerbated the tendency for humans to be overly concerned about their health. What they couldn’t see is what happens when a culture starts producing this type of person at scale.

That moment arrived in the late 19th century with the rise of neurasthenia.

The symptoms of neurasthenia might feel uncannily familiar to a citizen of the 21st century. Chronic fatigue. Anxiety. Depression. Insomnia. Digestive trouble. Sexual dysfunction. Doctors blamed railroads, telegraphs, factories, newspapers, urban living, and intellectual work. The nervous system, they said, simply wasn’t built for this much stimulation.

And, just as Plato might have predicted, neurasthenia showed up most often among professionals and intellectuals who worked white-collar jobs and had more disposable income and leisure time than their blue-collar counterparts. People like clerks and managers. These were people with relatively comfortable lives and scant physical demands compared to their less well-off counterparts. With fewer concrete responsibilities and outright aches and pains to arrest their attention, people had the stillness, time, and bandwidth to start noticing and focusing on more nebulous wrinkles in their physical and mental health and what could be done about them to feel better.

The cure for neurasthenia was involved. Doctors would prescribe rest cures at sanitariums. Strict diets. Colon cleanses. Men could get electric belts that would zap their penis to help them with their “potency,” and women were prescribed vibrators to cure them of their “hysterics” through orgasms.

The 1994 movie The Road to Wellville hilariously captures the strange health fads of the late 19th century. And if you squint, you can see 21st-century wellness culture there as well.

That wave of steampunk biohacking eventually crested and receded, but the underlying pattern didn’t disappear. It just resurfaced again in the mid-20th century with the rise of Boomer “healthism.” Social critic Christopher Lasch was the diagnostician of this period.

In The Culture of Narcissism, Lasch made a Nietzschean argument that as traditional sources of meaning and authority weakened, people didn’t become carefree or liberated. Instead, they became anxious and preoccupied with the self. In short, narcissists. Life turned into a therapeutic project. But the goal wasn’t excellence or virtue or service. It was just coping.

He also noted that mid-century Americans no longer saw themselves connected to history. They didn’t see themselves as part of a lineage that had ancestors behind them and descendants in front of them. By his reckoning, many people lost the idea of leaving a legacy. Without a sense of building the world for future generations, people started directing their energy toward living as long as possible themselves. Health and an extended lifespan became the ultimate goal. Lasch presciently noted, “People today hunger not for personal salvation . . . but for the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal well-being, health, and psychic security.”

At this point, it’s tempting to conclude that caring about health at all is a mistake. That the safest move is to reject optimization, mock the wellness crowd, and start smoking unfiltered cigarettes, because after all, we haven’t put a man on the moon since we put the kibosh on smoking.

But that’s not what Nietzsche thought. And it’s not what Plato thought either.

The problem isn’t being concerned about your health. The problem is making health the all-consuming telos of our lives. When health becomes the goal, it shrinks life. But ordered properly, Nietzsche believed health could do the opposite. It could enlarge life.

Which is why Nietzsche didn’t argue for less concern with health, but for a very different kind of it.

Nietzsche’s Great Health

The great health—one does not merely have it, one acquires it continually, and must acquire it continually, because one gives it up again and again.

For all his talk of barbarians and will to power and eagles flying from mountains and gods that laugh and dance, Nietzsche was a sickly fella. For most of his adult life, he suffered from migraines so bad that he’d have to hole himself up in a dark room for days before they’d go away. He also had stomach problems. Lots of vomiting and constipation. He went blind and had to start using a typewriter (which changed his writing style, something I wrote about last year).

To counter his chronic health problems, Nietzsche did some very Last Man, Platonic Valetudinarian, Laschean Culture of Narcissism, Dave Asprey biohacking things. He went to health spas around Europe to hike in high-altitude air, bathe in mineral waters, and eat regimented diets of gruel.

None of it helped.

Ol’ Friedrich noticed that his preoccupation with his health was making him play small ball with life.

In The Gay Science, Nietzsche introduces an idea that he calls große Gesundheit or Great Health. When you read it knowing Nietzsche’s own health problems, you can’t help but think he was writing this to himself.

For Nietzsche, Great Health isn’t about perfect functioning. It isn’t about extending life indefinitely or eliminating suffering. It’s about building up the vitality you need to commit yourself to demanding projects that might fail and might cost you something. Great Health is about having the strength to endure hardship and the resilience to take an existential gut punch without folding.

Great health is health for using.

Health ordered this way stops being anxious and inward-facing. It has an aim bigger than and beyond itself. It becomes purposeful. Nietzsche thought that without higher ends, health falls into morbid self-consciousness and becomes neurotic. But when subordinated to creation, duty, or love, it becomes noble.

This idea wasn’t unique to Nietzsche.

Centuries before him, the 16th-century Venetian nobleman Luigi Cornaro came to a similar conclusion by experience. Thanks to hard drinking and gorging on meats and fatty sauces, Cornaro was in rough shape. He had gout. The doctors told him he was a goner. But Cornaro didn’t accept the doctor’s diagnosis. He reformed his habits. He changed his diet. He walked daily. Took care of his sleep. Managed his stress. All the boring stuff that still works. Given a death sentence at age 40, Cornaro went on to live until he was 100 years old. He even wrote a book about his health system that was a big hit for centuries.

But Cornaro didn’t pursue health just so he could live a long and comfortable Last Man Life. He pursued it so he could remain useful.

Cornaro believed health was a gift meant to be returned — a means to serve God, family, and republic. And he did that. He designed hydraulic systems to recover wetlands and even wrote a comedy in his 80s. Health was not a project in itself. It was a means to an end.

The same orientation towards health shows up in Theodore Roosevelt’s idea of “the strenuous life.”

Roosevelt’s story of transforming himself from a sickly, asthmatic nerd to the burly, rough-riding Bull Moose is legendary. As a boy in his Manhattan brownstone, he started swinging Indian clubs and exercising on the parallel bars. As he got older, he got into boxing. He went on long hunts in the winter in Maine.

But what’s interesting about Roosevelt’s embrace of strenuous living was that it operated within a decided frame: the idea that health and strength should be used for the greater good. TR used his to serve in public office, write books, explore unmapped locales, and raise six kids.

For Nietzsche, for Conaro, for TR, you built your body so you could build the world around you. You didn’t just seek health, you sought Great Health — the health that facilitated greatness.

Health as a Means, Not an End

I lift weights religiously. I walk every morning. I track my macros. I prioritize my sleep.

And while I’ve spent 3,000 words critiquing the weirdness of modern wellness culture, I still dabble in it. I’ll wear my Oura ring every now and then to see how my HRV is. I take cold showers, occasionally. I’m even experimenting with red light therapy. It’s fun. It’s interesting.

But I try not to make my health the dominating interest of my life.

Yes, I want to be healthy, but I want to be Great Health healthy. I want health so I can use it. To have the stamina and clarity of mind to work long, fruitful hours. To have the energy to serve in my church congregation. To help a friend move their heavy ass antique piano from their third-story apartment. To do fun physical activities with my kids on trips — and someday take my grandkids on adventures too.

I want to be healthy so I don’t have to think about my health and can think about the important things in life.

So by all means, take care of your body. Wear that WHOOP band and look at the sky for photons if you want. Just don’t be a weirdo Last Man about it. Have an aim beyond health itself.

Build enough health to give yourself away in work, love, and service.

I love that you distill all the advice down to "don't be a weirdo." I remember seeing Joel Salatin speak and what he said stuck with me. "You can be a Buddhist or you can be a Nudist but you can't be a Buddhist Nudist. It's just too weird." I'll try to not be too weird.

Great perspective going into this year. Thanks for all the work you put into this writing!!